Show Notes

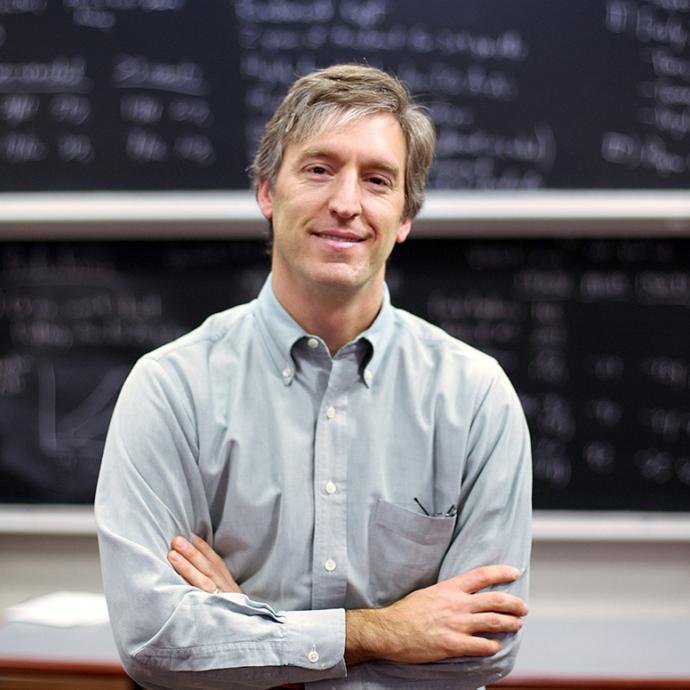

Of the academic books that have become household names, “Freakonomics” must be at the top of the list. The 2005 book by University of Chicago scholar Steven Levitt and journalist Stephen Dubner created not only a whole new way of thinking about discovering answers to complex problems, but launched a media empire—from book sequel to a movie to a hit podcast.

On this special episode, we sat down with Levitt during the inaugural UCPN Podcast Festival, to talk about the legacy of Freakonomics. Almost 20 years later, he told our audience how he views himself as a “data scientist” and not just an economist, what he’s learned about using a coin flip to make hard decisions in life, and why he thinks he may have found the “holy grail” of solving crime.

Subscribe to Big Brains on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

(Episode published October 19, 2023)

Subscribe to the Big Brains newsletter.

Please rate and review the Big Brains podcast.

Link to the advertised Chicago Booth Review Podcast: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/podcast?source=cbr-sn-bbr-camp:podcast23-20231019

Related:

- Freakonomics website

- Listen to Freakonomics Radio

- Why indecision makes you smarter—BBC

- Thinking of making a big change in your life? You’ll be happier if you go for it, a new study says—CNN

Transcript:

Paul Rand: It's rare for a book about academic research to become a household name. But that's more than the case for Freakonomics. It's the kind of book that nearly everyone in your family may have heard of. Here at the University of Chicago, we're lucky to be home of one of its authors, Professor Steven Levitt. On this episode, we got to sit down with Levitt in front of a live studio audience to talk about the legacy of Freakonomics and what it means to "think like a freak", what the science says about how to make that decision you've been dreading, why Levitt's work piqued the interest of the CIA in the early 2000s, and why he thinks his most recent research is the "holy grail" of crime prevention and a possible solution to our mass incarceration problem. Welcome to Big Brains, where we translate the biggest ideas and complex discoveries into digestible brain food. Big brains, little bites. From the University of Chicago Podcast Network, I'm your host, Paul Rand. On today's episode, the past and Future of Freakonomics Research.

Paul Rand: Well, it’s interesting. For a guy who is really one of the world’s most noted economists, you don’t necessarily think about yourself as an economist, do you?

Steven Levitt: I think I’m an economist by training, but I identify more as a data scientist. The thing I love to do is get a pile of data and make sense of it. I’m actually really out of step with my own profession. I don’t value the same things, and I think they don’t like me that much, and I don’t like them that much.

Paul Rand: What do you mean by that? Talk about that for a second.

Steven Levitt: Economics is a field in which entry is largely determined by how good you are at math. To get into a PhD program these days, you have to be incredibly good at math.

Paul Rand: What was your class, 1A, you took at Harvard?

Steven Levitt: Math 1A. I took exactly one math class in my college career. It’s called Math 1A. It was high school math over again because I hadn’t learned calculus when I took it in high school. I showed up at the class and it was all men, and they were all like 6’3” tall and weighted like 215 pounds. It was because it was me, and the hockey team, and the football team were the only people who were bad enough at math at Harvard that they were put in this class.

I was the best in the class, number one in the class, but I was smart enough to know that I couldn’t compete with other people in math, so I didn’t take math. I only went to get a PhD in economics because I had gone into management consulting and I hated it. I needed something else to do and I thought, well, the only thing I was really good at was economics, so I’ll go get an economics PhD. It was a terrible match for me because I was interested in technicality. I wasn’t interested in math. I really was interested in data, but there was no such thing as a data scientist. I’m old. This was many years ago. 30 years ago, there really wasn’t such a job as being a data scientist.

Austan Goolsbee, who many of you might know, Austin was in my class, and he was an anointed one. Austan had all of the right skills and preparation. He and the other anointed ones sat down one day to make a list of who the failures were going to be. There were four of us on the list, and Austan told me I was right on that list of the four. That actually did give me a kind of freedom to be myself.

Paul Rand: You weren’t devastated by that.

Steven Levitt: Well, they didn’t tell me until later. It only came out a few years later, but no, I would have said the same thing. It was obvious. It was not unclear to anyone that I was a black sheep in this group, but it gave me the freedom to be myself. I think that’s something that young people in academics rarely feel empowered to do.

Paul Rand: Yes.

Steven Levitt: I was really lucky and I had a niche within economics, thinking of offbeat problems and finding ways to answer those questions using data that other people hadn’t usually used before. In a weird way, it was very marginal and yet, I was able to get my papers published in good journals, and perhaps, inspired people to think that you could ... Like Gary Becker, in Gary Becker’s huge footsteps. My little, tiny footsteps followed them of inspiring people to think you could apply economics to all sorts of settings.

After we wrote Freakonomics, I’d always loved being an academic, but I realized it was more fun. Freakonomics was more fun. The opportunities, the whole new opportunities that opened up for me, I just found they were more fun.

Paul Rand: Let’s talk about this. When you think about, what’s economics and what’s Freakonomics, because you really have become synonymous with that brand, how did you come up with it and how do you think about it then and today?

Steven Levitt: I had been in the profession for 10 years, and I had published probably 40 papers. They were just all the things that interested me, and many of them were the things that showed up in the book, like real estate agents were ripping off their clients, and sumo wrestlers were cheating, and Chicago public school teachers were erasing the answers to make themselves look better, and a bunch of stuff on abortion and crime, and all this stuff. I had just done this without any spirit other than excitement. I loved getting my hands into data and answering these questions, but it didn’t really have much of a point, so then everything changed when ... So I won this prize.

Paul Rand: What was the name of the prize again?

Steven Levitt: John Bates Clark Medal.

Paul Rand: Okay.

Steven Levitt: The New York Times wanted to write a piece about me. I more or less said no, but they were persistent. I really did it for my mom because my mom loved reading about me in the newspaper, and so I thought, “Okay. I’ll take one for the team. I’ll do this so my mom can read about me in the newspaper.”

Interestingly, Steven Dubner, who was asked to write it, he said no repeatedly too. He didn’t want to do it. Then he said, “I’m going to be in Chicago, and could we spend the morning of Thursday?” I said, “Sure,” and so we spent the morning and it was great. I was like, “Okay. See you later.” He said, “Well, actually, I don’t have that much else to do. Would you mind if I went to lunch with you?”

There’s a terrible problem when you’re being interviewed for The New York Times. You’re in a very subservient position because you have to be as nice as possible to the reporter. You don’t want them to write something terrible, so I’m like, “Okay. I guess, you could come to lunch with me.” Then when lunch was over, I said, “Well, see you later. Hope the article’s really good.” He said, “Well, I actually don’t have any plans. Could I just come and sit with you in your office?”

I said, “Well, you could, but what I’m going to do for the rest of the afternoon is I’m going to sit at my computer and I’m going to type in the data, play with the data. I’m not going to say a word to anyone, so I don’t think it’ll be very entertaining.” He said, “Oh, no. No problem. I’ll just come. Won’t say anything,” but of course, he was. He continued to ask me questions and he was really ... I have to say, he had read every paper I’d ever written, seemed to understand every paper I’d ever written.

As soon as I stopped answering one question, he would ask me another one. He was never at a loss for a question, and it didn’t end then. He said, “Well, I don’t have any plans tomorrow. How about we meet again?” We spent the entire day the next day, by 3:00 p.m. on the Friday, so he had now been there for however many hours. I said, “Hey, I’m getting kind of tired. Should we just go to the racetrack and have some beers?”

We ended up getting drunk and betting on the horse races, and that’s when I made this mistake. I started getting a little more relaxed and loose-lipped. He asked me what I thought of the CIA, and I blurted out that if I were in charge of catching terrorists, I’d be better than the CIA. As soon as I said that, I was like, “Why did I say that? That was really stupid.” I thought, he had taped me for all these hours. What are the chances that that one little blurted line would get in there? It ends up being the last sentence of the article is me throwing down the gauntlet to the CIA. Anyway, it was interesting. Two days later, the CIA called me on the phone to talk with them, so it actually turned out better than-

Paul Rand: What did they want to talk to you about?

Steven Levitt: They were trying to catch terrorists and they were working on a program around ... None of this is classified. I think I can freely talk about it. They were hoping they could catch terrorists by using financial markets as an early warning signal. If someone was going to blow up a bunch of McDonald’s, then they would short McDonald’s stock a week ahead of time, and that would put out a red flag, and so they invited me and a bunch of-

Paul Rand: Oh gosh. Okay.

Steven Levitt: ... other people down to the CIA to see if that would work. The most interesting thing that happened, as all of the experts were talking about how we would trade on a terrorist attack if we were the financiers and the way we wouldn’t get caught, one of the people who was the experts said, “You guys are all a bunch of idiots.” We kind of bristled like, “What do you mean we’re idiots? We’re the ones who are telling the CIA their thing’s not going to work.”

He was sitting in his office when he saw a plane crash into the World Trade Center. He said, “I jumped on the phone. I called my traders and I said, “Trade everything you can as fast as you can, as fast as you can.” By knowing an attack had happened, it took something like seven or nine minutes before the markets shut down. They made enormous, inordinate amounts of money. 20, $50 million in those seven minutes trading.

Paul Rand: Wow.

Steven Levitt: He said, “You’re all a bunch of idiots because why in the world would you trade in advance of a terrorist attack? If you know a terrorist attack is going to happen, first of all, it might not go off, and so why would you want to trade and lose money? Secondly, if you have people on the ground tell you it happened, you have 10 minutes. You can do all the trading you want. You can make as much money as you want, as much off your capital, and then how is anyone going to say you’re a terrorist financier? It’s not your fault that you happened to see the attack happen. Oh, it’s just luck.” It was really interesting.

Paul Rand: That is very interesting.

Steven Levitt: It was one of the moments where I thought about this problem a lot and then somebody smarter with me, or at least with different experiences, immediately saw the right answer.

Paul Rand: Well, part of this idea, I guess, getting into what is this concept of when you put the freak in front of it and then you think about, well, how does the person with this mindset look at some of these problems differently than somebody else? It really is this idea of decisions and incentives, I guess. Is that how you think about it?

Steven Levitt: Yeah, I would say the ideas that motivate Freakonomics are exactly the ideas that are central to microeconomics. It’s about incentives.

Paul Rand: Can you, by the way, explain for folks the difference between macro and micro?

Steven Levitt: Sure, sure. Microeconomics is the study of individual decision-making. When faced with trade-offs or constraints, how to people make the best choices? That would be people or businesses.

Paul Rand: Part of this idea is how people are making decisions and thinking about it. There are things that you’ve done like coin toss studies and so forth, right?

Steven Levitt: Yes. Let’s take that. I just described economics as a discipline that’s about decision-making. What do you do when there are trade-offs? Yet, if somebody comes to me and says, “Should I do this or should I do that?” I have absolutely no idea what to tell them because without knowing their utility function and all of their opportunity set, I don’t have anything to say. That seems like a real failure of a discipline that thinks it should be trying to help people make better decisions.

Steven Dubner has his Freakonomics podcast. He does whatever he wants on that podcast, so it’s very different than our book. All of our books were anchored in academic studies, but after you do a podcast for 10 years, you got to start doing ...

Paul Rand: Right, right.

Steven Levitt: Dubner just, on his own volition, decided that people didn’t quit enough, and so I would say with zero evidence, did a podcast in which he just asserted, and interviewed a bunch of people, and made the point and concluded that people didn’t quit enough. We started getting emails, dozens of dozens of people saying, “I listened to your podcast and I quit my job.”

I even ... One of my consulting friends in venture capital, who I had immense respect for, wrote me and said, “I just listened to your podcast and I quit my job, and I’m starting my own venture capital firm.” That was so shocking to me that it actually opened up a whole new way of thinking because I realized, wait a second. Dubner’s podcast, our podcast, it was mostly his podcast, is so powerful, he can get people to do whatever he wants. I thought, “That is amazing,” so now, I have a whole new tool, which is I can take this media franchise and the question I’m interested in is, is it true? Do people quit too much or too little? Dubner believed that they quit too little, but how could you test it?

It’s not even obvious how you test that question if you have a randomized experiment. If I took this half of the audience ... Let’s say the question is, should you get divorced? I take all the married people on the left side of this room. You all go get divorced. I take all the people on the right side. Even if you want to get divorced, you’re not allowed to get divorced. We roll things out 10 years, we see how things go. That wouldn’t even answer the question because I don’t want to know whether getting divorced is good on average for people.

I want to know for people who just can’t decide. They’re right on the margin. For those people, those are the people who are trying ... who we want to know, should they get divorced or not? Because it would be really helpful to know if it’s the right thing to do, and so what we ended up doing ... Everybody told me it was a terrible idea. This is of all the things that I’ve done in academics, this is the one that I was most told was a terrible idea, is we spent months and months building a website.

All it really did after a lot of smoke and mirrors, because we didn’t want the people who were in the study ... They knew they were in a study, but we didn’t want them to know why they’re in a study ... was at the end we said, “Well, do you have a problem you can’t decide on?” We gave them lots to choose from, but a serious problem like quitting your job, ending a relationship, whatnot.

After we asked them a bunch of questions to make them feel like we were helping them try to decide, what we really wanted them to say is, “I still don’t know what to do,” and then we would literally toss a coin for them on the website. If it came up heads, we would tell them to get divorced. If it came up tails, we’d say,” Don’t get divorced,” and we did this. First of all, you could say, well no one-

Paul Rand: You actually told people to get divorced?

Steven Levitt: Absolutely.

Paul Rand: Okay.

Steven Levitt: But we also told them not to get divorced, and that could be just as bad as telling them to get divorced. Amazingly, something like 25,000 people flipped coins on the website.

Paul Rand: Oh my gosh.

Steven Levitt: About two-thirds, 60% to two-thirds actually followed the coin toss. The people who got heads were more likely to get divorced than the people who didn’t, who got tails. The people who got heads were more likely to quit their jobs than the ones who didn’t. Partly, it’s a lot of complicated issues about reporting, whatnot, but really, the best thing we did in that study was to ask people to also give us a trusted third party who would help them make their decision, or help support them in their decision.

What that meant was six months later, I could email the friend and say, “Hey, did your friend get divorced or not?” Because I don’t really necessarily believe the person, who knows I told them to divorce, could easily lie to me and say it, but I doubt their friends would lie about it. It turned out that across every decision, essentially, the people who got heads were happier six months later than the people who got tails.

The people who got heads also changed their behavior more. They either got divorced more or they quit their jobs more than the people who got tails. You would have expected, on average, the people who got heads and tails to be exactly as happy six months later because they were, in principle, exactly as happy at the time they did the coin toss because it was randomized. The only real conclusion after you do some hard work on trying to make sure there aren’t biases in there in who’s responding and, “Are they lying to me?” and whatnot, but I’m at least convinced that I think we did-

Paul Rand: Okay.

Steven Levitt: We were able to work with that. Is that these people who thought they were on the margin, who weren’t sure what to do, who were really indifferent between the change and not a change, so indifferent that when this silly website flips and comes heads, they actually do the decision more or less than otherwise. Those people, when they made a change, were much happier than the people-

Paul Rand: They wanted to make a change, but needed a nudge.

Steven Levitt: Well, I think that every bias that is around us pushes us against change, so oftentimes, you pay the costs right away and you get the benefits in the long run. You’ve been brutally trained from an early age that winners never quit and quitters never win, that perseverance is a good thing. I think we just are all off.

The beauty of this study, for me, is that now, anytime anyone asks me for advice about a decision, my rule is really easy. I try to figure out whether they’re really on the margin, whether they really can’t decide. I try to figure out which path represents the biggest break from what they’re doing right now, and I just say, “You should make the change.” For me, it’s one of these simple rules of thumb that guides my own life, and I think should guide everyone’s life, which is that if you think you’re indifferent, then you’re long overdue to have made a change.

Paul Rand: If you're enjoying the discussions that we're having on this program, there's another University of Chicago Podcast Network show that you should check out. It's called The Pie. Economists are always talking about the pie, how it grows and shrinks, how it's sliced, and who gets the bigger share. Join veteran NPR host Tess Vigeland as she talks with leading economists about their cutting edge research and key events of the day. Hear how the economic pie is at the heart of issues like the aftermath of a global pandemic, jobs, energy policy and much more.

Paul Rand: How can we improve communications at work? Are stock markets really efficient? Should we let algorithms make moral choices? How will climate migration affect our societies? The Chicago Booth Review Podcast addresses the big questions in business policy and markets with insights from the world's leading academic researchers. We bring you groundbreaking research in a clear and straightforward way. It could help you make better decisions, work smarter, and maybe even become happier. Find us wherever you get your podcasts or at this link: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/podcast?source=cbr-sn-bbr-camp:podcast23-20231019

Paul Rand: You have done your work in tons of different fields. One of the ones you’re really known for is your work in crime, and my understanding is you got into crime research because you like cop shows. Is that ... some accuracy to that?

Steven Levitt: Yes. It was at this moment of truth for me in grad school when I realized I wasn’t probably going to be very good at economics. That did give me the luxury to try to study whatever I wanted, but I didn’t know what I liked, and I realized, well, I watch the TV show, Cops, every day on TV. That’s what I’m interested in. That’s what excited me, and so I got ... Even though there’s very little economic research done on crime, in part, because it’s not a market, but the kind of data methods that economists use turned out to be really helpful in that. Really, I thought of myself as a crime economist for the 10 or 15 years I started studying that.

Paul Rand: Okay. As you think through that period, what were some of the bigger insights in crime that really intrigued you?

Steven Levitt: The two questions that I was really interested in was, number one, why did crime go up so much in the 1960s?

Paul Rand: Okay.

Steven Levitt: Then, why did crime go down so much in the 1990s? I tried hard on why it went up in the 1960s. Never figured that one out. Never made any headway on that. What I tried to do about the 1990s was just tick off every possible explanation. Increases in police, increases in prisons, demographic changes. None of those really worked.

Then that’s where my most famous study eventually came from, where I stumbled onto basic data on legalized abortion around in the ‘70s, and more in the ‘80s, the peak in the ‘80s. It was something like one in three, one in four pregnancies in America ended in abortion. That was really stunning to me. I had actually looked at whether that might be related to crime. Couldn’t find a relationship, and put it down.

Actually, it was a chance encounter with another economist, John Donohue. We were working on a different paper and I still remember the exact setting, sitting in the office where he said, “I have the craziest idea ever. I really think that maybe legalized abortion in the 1970s is why crime went down in the 1990s.” I said, “Yeah, I had that same idea.” I had a whole folder of stuff that I looked at, and it turned out I had looked too early. Donohue understood the theory better than me, and he had done a lot of research into what we call unwantedness.

It turns out that unwanted children are at enormous risk for all sorts of bad life outcomes, whether it’s suicide, or crime, or early childbearing themselves, things like that. John had already assembled evidence that showed that after legalized abortion, there was a huge decline in the number of unwanted children. For instance, domestic adoption plummeted after legalized abortion.

Then we looked at the data, and it really became just clear in the raw data, now that more time had passed, that this was a really important potential phenomena. It’s a super simple story. Unwanted children are at risk for crime. Legalized abortion reduced the number of kids who were unwanted and so, therefore, legalized abortion should have reduced crime. It was just an empirical question. Was it a big effect or a small effect? You could calibrate it based on some of the earlier studies on unwantedness that had been done in Europe many years earlier, not about crime, but just about other life outcomes. It really seemed like it could be big. Then when you looked at the data, it really was big.

Paul Rand: We’re going through another transition in that world. What do you think about when you see how difficult it is becoming to carry through on abortions today?

Steven Levitt: I think two things, maybe three things. One is if it does indeed turn out to be true and persistent effect that it’s hard for some women to get abortions in this country, then I would strongly predict that those cohorts will be high in crime. But far more important is that people shouldn’t get confused about my research having policy implications. Of all the reasons you would say that we should or shouldn’t have legalized abortion in the United States, the affect on crime is just so far down the list. It is so unimportant relative to either the arguments about a woman’s right to choose, or on the flip side, the view that abortion itself is some kind of murder, some form of murder.

Look, I don’t know the answer. That’s not my job to decide which of those is true, but those two perspectives so eclipse the very minor relative impact on crime that it would be misguided to use my research to support either of those positions. It’s just unimportant. My research, I think, is very important for thinking about why crime has gone up and down and whether, say, other policies like mass incarceration should get the credit for it.

Paul Rand: Let’s talk about this because you have a new project, and it’s called Radical Innovation for Social Change. Even that title says you’re thinking there can be social change out of some of your insights. Or how do you think about what you’re doing there and what you’re hoping is going to happen?

Steven Levitt: What I’m trying to do is combine three world views into one.

Paul Rand: World views?

Steven Levitt: World views.

Paul Rand: Okay.

Steven Levitt: One is an academic world view of rigor, of ideas, of trying to do things right. The second is an NGO or a non-profit view of the world, which is, “I’d like to actually have some impact and do some good.” I’d say, realistically, my own academic work has a very little real-world impact. It’s got a lot of attention, but it hasn’t changed policies. I don’t think it’s changed a lot of lives.

The third world view is this startup idea, where you do things quickly, and you’re innovative, and you do it on a shoestring in a few years. We’re trying to put those three together. We’ve been at it now about five years, and we’ve tackled a bunch of problems. I can give you some examples.

Paul Rand: Please do.

Steven Levitt: Let’s go back, let’s stick with crime and talk about crime. Crime imposes an enormous cost on society, but efforts to control crime like incarceration and whatnot, they also come with enormous costs. The Holy Grail of crime is, how do you just convince people not to do the crime in the first place? We call it deterrence. It turns out both empirically, and it makes common sense, that almost nobody would do a crime that they know they’ll be caught for. For instance, people do not rob the Dunkin’ Donuts when the police are in the Dunkin’ Donuts. It’s just empirically, you’d see that probably doesn’t happen.

Imagine that you actually could just take people who are known criminals, and you just assigned someone, and the police officer followed them around all day long. They wouldn’t do much crime. The thing is, with technology, we more or less have that ability in the form of GPS. There are a set of people in this country right now who are wearing ankle bracelets. Interestingly, these are people, say, who are either on pretrial release or they’re on parole, and they’re wearing these ankle bracelets.

The crazy thing that most people don’t realize is that they’re not mostly equipped with GPS. They actually use this old technology called RFID technology. There’s a beacon in their house. They’re essentially under house arrest. If they go more than 60 feet from the beacon, it sends a signal that says they’re more than 60 feet from the beacon, but then the sheriff can’t find them because they don’t have GPS on. It makes no sense.

Paul Rand: Okay.

Steven Levitt: Then we just actually started a pilot with the Cook County sheriff, Tom Dart. We switched the bracelets over to GPS and what you can do is you not only now can follow people around and know where they are, but we have the ability to link those up to the police databases. In Chicago, for instance, there’s something called ShotSpotter. Every time a gunshot occurs in Chicago, it’s triangulated using echolocation, and I know exactly where that shot went. Now we could, in real time, cross-reference where shots are taking place to whether or not there’s someone who’s on pretrial release who is wearing an ankle bracelet that’s GPS-equipped, and know whether they were there.

Now, being there doesn’t mean they were the person shooting. They might have been shot at, but it certainly seems of great interest to all involved to, number one, know that they were at the scene of that shooting and, number two, to know how to find them very quickly to go ask them what had happened actually at the scene of that shooting. The most important part is you tell them, “Look, you are wearing GPS. Don’t do anything stupid. We will know if you do something stupid.” That, by and large, they do very little in the way of crime while they’re doing that.

What’s interesting is that I say that now, many people who are left-leaning are feeling disgusted and revolted by, “Oh, Big Brother,” da, da, da, da, da, but what this really is, it is the source of freedom for a large group of people who would otherwise be locked up. We’ve had 15,000 people through our program. Everyone has been given the choice, would they rather be locked up in jail or would they rather be on these bracelets? 15,000 out of 15,000 said, “Yes. Please let me be out of jail on the bracelet,” so if I put GPS on people, then they won’t commit crime.

That means I can let out enormous amounts of people from prison. Because, more or less, the reason we have people in prison is because we’re afraid they’re going to do crime if we release them. You can go back and now you can completely rethink the whole criminal justice system. The first time somebody does a crime, you would never lock them up and disrupt their life, take them out of school, make them lose their job, send them down state, away from the community.

You would give them some chances where now, “Oh, you made a mistake? Well, now we’re going to monitor you. As long as you don’t make another mistake, you can just basically live your life.” So really, to me, this could be the thing which allows us to, from my rough estimates, I think we could, if we wanted, reduce crime by 50% by using this. Reduce the prison population by 40%, or some combination of those two things. It would be the biggest policy impact.

What’s interesting is we’re doing it in Cook County. It’s working, but we can’t really convince anybody that it’s a good idea, so nobody likes it. The left hates it because it feels like, “Big Brother, my god.” Look, I’ll say I’ve worn these ankle bracelets just to ... They are like shackles. They are the most horrendous, dehumanizing thing in the world, but they shouldn’t be shackles. They should be like Apple Watches. There’s no reason you couldn’t do this with just like everybody wears light, friendly, imbued with all sorts of other things that are useful. Then the right doesn’t like it because it’s-

Paul Rand: Too easy.

Steven Levitt: It’s too easy. It’s dismantling the prison industrial complex, and so it’s funny that we just ... It’s an idea that, to me, feels like a winner, and we haven’t figured out the marketing to get anybody else to like it.

Paul Rand: All right. We have got, goodness, about 10 minutes left. I bet you there’s a lot of folks ... Would you mind if you took some-

Steven Levitt: Sure, great.

Paul Rand: ... questions from the room?

Steven Levitt: Please.

Paul Rand: Is Matt around with the microphone? Folks, as you listened to this conversation, or maybe you walked into the room saying, “I always wanted to ask him about this,” please take your shot.

Speaker: Yeah. You mentioned that you think of yourself more as a data scientist than an economist. I happen to be a data scientist. A lot of what we do is not the kind of looking at and playing with data that you’re talking about. It’s a lot of like, “Here’s a dataset. Model it,” and maybe you don’t actually know what’s going on. It seems like you’re describing something that’s like almost different than what a lot of data scientists are doing.

I’m curious if you have any thoughts on ways to teach the kind of intuition for, I guess, almost like the interpretable, causal type of stuff that you’re looking for in data as an economist that might be helpful for data scientists to think about.

Steven Levitt: I think you’re right. The notion of what data science encompasses is really, really big. What I do is a very particular part of that, which is I try to find data, a pile of data, and make sense of it. Or, often, I’m motivated by a question and that question leads me to a pile of data, which I either try to generate data or make sense of it. Whereas, what many data scientists do ... Often, data science involves prediction, so really nothing I do involves prediction. Much of what corporate data science does is trying to predict what will customers do, what will competitors do.

Let me just acknowledge that I think that’s true, that data science takes all sorts of forms. I think there’s a common theme to it, which is a good data scientist is highly attuned to quality and the structure of the data that they’re using, and making sure that it is the right data to apply to a problem. Then using different notions from statistics or different techniques to try to look at the correlations in the data. Then to say, “Look, correlation is often not what we want. We want causality.” Causality is more difficult to ascertain than correlation. What kind of techniques can we, in this setting, do well to do it?

The second question is, how do you teach data science? I don’t know if I have ... I don’t have any answers to how you would do it, but what I very strongly believe is that we should be doing it. I think it’s an absolute travesty that you can graduate from high school in this country and not know anything about data, barely have been exposed to data. I think it’s an absolute travesty that the math we’re teaching children today is exactly the math that I was taught 40 years ago in high school. It’s pretty much the math that was taught 75 years ago in high school, my father was in high school.

One of the things that we’ve done through my Center at RISC is we’ve brought together a consortium of like-minded people, and we’ve created this institute called the Data Science for Everyone, which is now out there trying to do the hard work on the ground to get data science curriculum into the schools. It’s something I’m very passionate about, very excited about because I think we’re just doing such an enormous disservice to young people in continuing to teach them to do proofs about triangles and angles of triangles, which no person ever will use again, when we could be showing them datasets. It’s just mind-boggling to me that that useful skill is not seen as a central part of what school should be doing to kids.

Paul Rand: Good. Please. Yes, sir.

Speaker: Thank you for your time. This is really fascinating, and your work. Regarding the GPS ankle bracelet, I’m fascinated by this idea. First of all, I wanted to find out if anything’s been written or published about it.

Steven Levitt: We have not published anything. We’ve been working with Cook County now for two or three years. It wasn’t done in the nature of a controlled study, for instance. It was an opportunistic chance for us to work with them. We’ve analyzed it, so I can look and I can see of the ... Say if there’s been 15,000-person years of data for Cook County where they’re wearing these bracelets, we can look and see how often those folks have been rearrested, or how often they’ve been at the site of shots going off. The numbers are really low. I would say-

Speaker: There’s no articles?

Steven Levitt: We haven’t yet. I felt like the first group that I need to convince are the criminal justice people, and I haven’t felt like academic articles will be the way to convince them. We’ve really felt like being on the ground, showing them how it works in Cook County, showing them the software that we’ve developed in Cook County that actually makes the job much easier for the Sheriff’s Office than it otherwise has been been a primary vehicle for trying to make the change. Yeah, I mean, I would say it’s early days. We’re just getting off the ground now.

Speaker: All right. What I wanted really to find out is, if this was in widespread use, had you thought about the idea that it would be pretty easy to set these people up in crimes? All somebody would have to do in a gang is to get one of them in a car with them and then go do a drive-by shooting and blame it on the guy who’s wearing the GPS bracelet, or walk into a convenience store, pull out a gun and rob it.

Steven Levitt: All we’re going to know is that they were in a car that was in the vicinity, but that would in no way be enough evidence for the sheriff to say that they shot the gun, for instance. In fact, I think it would be the exact opposite, which is that if this person said, “Yeah, I was in the car. I was in the car with this gang member, and this gang member shot the gun. If you go find that gang member, you’re going to find the gunpowder on their hand,” and whatnot.

I think it’s actually the way you want criminal justice to work, which is that this bracelet creates a witness to a crime, and also a witness who has a very strong incentive to tell you the truth because if he doesn’t tell you the truth, he’s going to be the leading suspect. In many ways, I actually think that your story is good. It’s more likely to help us solve crime than to be a miscarriage of justice where this innocent person gets blamed for a crime that he or she didn’t do because nobody believes him or her that it was actually another gang member who did it.

Now, if criminal justice works at all, then when the person who’s wearing a bracelet says, “Hey, the guy who actually shot the gun is this person, and this is where they picked me up,” and you can go see on cameras that are all over Chicago that this person drove their car that way, I just think it would help us. It’s the biggest problem we have in Chicago, particularly in criminal justice, is that there is a real lack of witnesses and people unwilling to come forward. One of the perverse things about these bracelets is that it gives the people wearing them extremely strong incentives to tell us who really did the crime because they are the focal point of the investigation until they can point you to the real person.

Paul Rand: Good answer.

Steven Levitt: So I think that’s really a good thing. Other people, it’s tricky. You get into tricky moral and ethical issues around this, for sure, but my own feeling is we’re already so deeply embedded in tricky, and moral, and ethical issues about how we treat the criminal justice system that these really are, to me, not deal-breakers.

Paul Rand: Coming on top of the hour. One final one. You have three iterations of your book. Last one that we talked about was 2015. Are there any more planned and what do we have to look forward from you?

Steven Levitt: I don’t think there will be any more books. I could not write a Freakonomics book alone. Steven Dubner is ... It’s just a shared enterprise.

Paul Rand: Got it. Okay.

Steven Levitt: He’s an amazing writer, and I don’t have either the writing talent or the ... It just wouldn’t be fun to do it-

Paul Rand: A team?

Steven Levitt: If we weren’t a team, but he found, initially, and he’s convinced me that podcasting is just a much better medium for us than book writing. Books do have their own virtues. They’re longer lasting. They stick around, but honestly, every book we wrote sold less than the one before it, so it’s not like it felt like we could just write books forever and people keep reading them, but the Freakonomics podcast reaches-

Paul Rand: It’s a great podcast.

Steven Levitt: It reaches more people in a month than many of our books did ever. It turns out that when you give stuff people for free, it helps. You give it to people for free, and he really delivers a great product.

Paul Rand: He does.

Steven Levitt: Then you have a way to reach people. Right now, to me, the idea of writing a book, of writing something that gets stuck in a moment in time that can’t really be uprated, that’s not ... Can’t be updated. It’s a lot of work. There’s a lot of like ... I find the freedom that comes with this medium, podcast, it’s actually a much better one for what we’re trying to do.

Paul Rand: So more podcasts to come.

Steven Levitt: I think so, yeah. Because, honestly, I also feel like our strength, my strength, Steven’s strength is really small things, not big things. Our books were a series of small things put together. Whereas, many books are one big thing.

Paul Rand: Gotcha.

Steven Levitt: When I have something I’m really excited about, whether it’s the ankle bracelets, or whether it’s an idea to save the rainforest, the Amazon rainforest, I feel like it’s a better venue is to try to go through the podcast, these days, for us.

Paul Rand: All right. We could talk a lot more. Is it all right if I come back to your office and just watch you work? Then we’ll go to the track, although it’s gone, and drink together.

Steven Levitt: Let’s do it.

Paul Rand: All right. It was great having you here.

Steven Levitt: Thank you.

Paul Rand: Thank you for joining us.

Steven Levitt: Yeah.

Matt Hodapp: Yeah. Thank you, guys.

Big Brains is a production of the University of Chicago Podcast Network. We’re sponsored by the Graham School. Are you a lifelong learner with an insatiable curiosity? Access more than 50 open enrollment courses every quarter. Learn more at graham.uchicago.edu/bigbrains. If you like what you heard on our podcast, please leave us a rating and review. The show is hosted by Paul M. Rand and produced by Lea Ceasrine, and me, Matt Hodapp. Thanks for listening.

Episode List

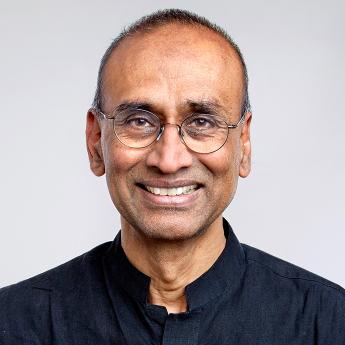

Why we die—and how we can live longer, with Nobel laureate Venki Ramakrishnan (Ep. 134)

Nobel Prize-winning scientist explains how our quest to slow aging is becoming a reality

What dogs are teaching us about aging, with Daniel Promislow (Ep. 133)

World’s largest study of dogs finds clues in exercise, diet and loneliness

Where has Alzheimer’s research gone wrong? with Karl Herrup (Ep. 132)

Neurobiologist claims the leading definition of the disease may be flawed—and why we need to fix it to find a cure

Why breeding millions of mosquitoes could help save lives, with Scott O’Neill (Ep. 131)

Nonprofit's innovative approach uses the bacteria Wolbachia to combat mosquito-borne diseases

Why shaming other countries often backfires, with Rochelle Terman (Ep. 130)

Scholar examines the geopolitical impacts of confronting human rights violations

Can Trump legally be president?, with William Baude (Ep. 129)

Scholar who ignited debate over 14th Amendment argument for disqualification examines upcoming Supreme Court case

What our hands reveal about our thoughts, with Susan Goldin-Meadow (Ep. 128)

Psychologist examines the secret conversations we have through gestures

Psychedelics without the hallucinations: A new mental health treatment? with David E. Olson (Ep. 127)

Scientist examines how non-hallucinogenic drugs could be used to treat depression, addiction and anxiety

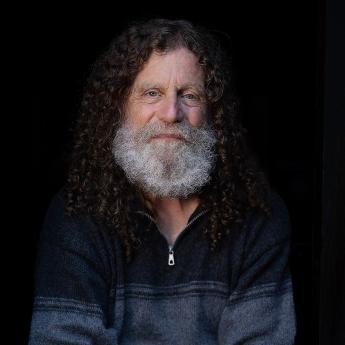

Do we really have free will? with Robert Sapolsky (Ep. 126)

Renowned scholar argues that biology doesn’t shape our actions; it completely controls them

A radical solution to address climate change, with David Keith (Ep. 125)

Solar geoengineering technology holds possibilities and pitfalls, renowned scientist argues