Willard G. Manning Jr., a leading researcher in health economics, died at British Home Rehabilitation in Brookfield, Ill. on Nov. 25. He was 68.

Manning taught at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and in the Department of Public Health Sciences before his retirement in 2011.

“Will was a beloved professor and an extraordinary researcher,” said Daniel Diermeier, dean of Chicago Harris. “In his distinguished career, he made many important contributions to our understanding of health insurance, poor health habits and mental health. We will miss a dear colleague and dedicated teacher.”

“What made Will stand out was not only the importance and rigor of his research but also the seriousness with which he approached his responsibilities as a member of the University and the larger academic community,” said Diane Lauderdale, professor of epidemiology and chair of Public Health Sciences. “The time and thought he put into mentoring junior faculty, advising graduate students and reviewing the work of others were extraordinary.”

With a focus on health economics, Manning is known for his studies that tested how the structure of insurance and costs affected demand for medical care and health. He developed a robust model to estimate optimal health insurance coverage by considering the tradeoff between the costs from moral hazard and the gains from risk pooling in health insurance.

In addition, his work involved rigorous examinations of statistical issues in modeling health and economic data, and the investigation of economic consequences of poor health habits, smoking, heavy drinking and lack of exercise. He was widely known for his work on the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, a randomized trial of alternative insurance plans conducted from 1974-1982.

Dan Black, deputy dean and professor at Chicago Harris, said Manning’s work with the RAND study “transformed our understanding of health insurance and has been the gold standard against which research in health economics and health services are still measured today.”

Black also commended Manning’s deep commitment to the teaching of statistics and the craft of research. “Will cared deeply that his research arrived at the correct conclusions, and he instilled this concern in his students,” said Black.

Manning published over 150 articles and chapters in his career and co-authored five books, including The Costs of Poor Health Habits by Harvard University Press in 1991. He received numerous awards for his papers on health economics, including the Victor Fuchs Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Health Economists in 2010, the Distinguished Investigator Award at the annual meeting of Academy Health in 2009 and the Kenneth Arrow Prize for the Best Health Economics Article in 2003.

A member of the Institute of Medicine, Manning served on different committees addressing the lack of insurance and health care at the end of life. He was also on a National Academy of Science panel that examined adding measures of medical risk to new poverty measures.

“Will’s scholarship made timeless contributions to our knowledge about how to analyze data on health spending and has allowed us to better understand critical health policy issues,” said David O. Meltzer, professor in the Department of Medicine, and affiliated faculty of Chicago Harris and the Department of Economics. “The methods he developed are essential tools for all health economists today.”

Meltzer, who was Manning’s research and teaching colleague for many years, said Manning’s devotion to his students was legendary.

“Will would provide amazingly detailed and thoughtful comments draft after draft of their written work and spend endless hours helping students solve their most difficult problems,” Meltzer added. “He set a standard for mentorship that is truly inspiring and is a model for all of us who have the honor of helping to train the next generation of scholars and teachers.”

For years, Manning had been plagued with health problems, but his daughters Lisa Manning and Heather Carlson describe their father as “an incredibly resilient man who overcame the obstacles with determination and positivity until the very end.”

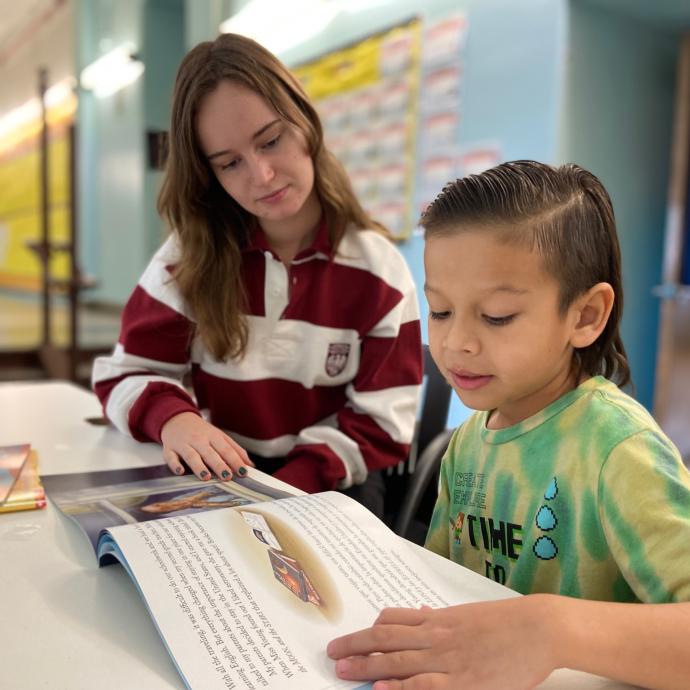

As a father, Lisa said Manning taught his children and grandchildren to embrace the joy of learning and encouraged many endeavors that they had pursued in life. “My father was incredibly generous, which I always found very inspiring,” remembered Lisa. “He lit up at the prospect of seeing his grandchildren in a school recital or soccer game. The times I saw him playing Legos with them were the times he seemed to be at his happiest.”

Manning is survived by his wife, Erika Manning; his daughters, Lisa Manning and Heather Carlson; his son-in-law, Brad Carlson; and his grandchildren, Emelia and Andrew Carlson.

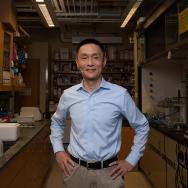

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He