It wasn't long after Robert Sengstacke met with directors of the University of Chicago's Special Collections Research Center that the son of a longtime Chicago Defender publisher decided his archive of family papers should remain in Chicago.

Center Director Alice Schreyer and Associate Director Dan Meyer played a crucial role in Sengstacke’s choice to keep his father John’s papers at the Chicago Public Library’s Vivian Harsh Collection.

[view:story=block_1]

The Abbott-Sengstacke Family Papers include tens of thousands of documents, more than 4,000 photos, and hundreds of family movies that provide a rare glimpse into African American history. On Wednesday, May 27, the Public Library announced the collection is now available for public use at the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, located in the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library at 9525 S. Halsted St.

Schreyer and Meyer helped Sengstacke weigh the merits of either selling the collection or gifting it to a repository. They answered questions about the technical aspects of gifting and helped him think through his goals for how the collection would be used.

But Goldsby says the University Library did far more than just provide counsel. “It made some astonishing contributions.”

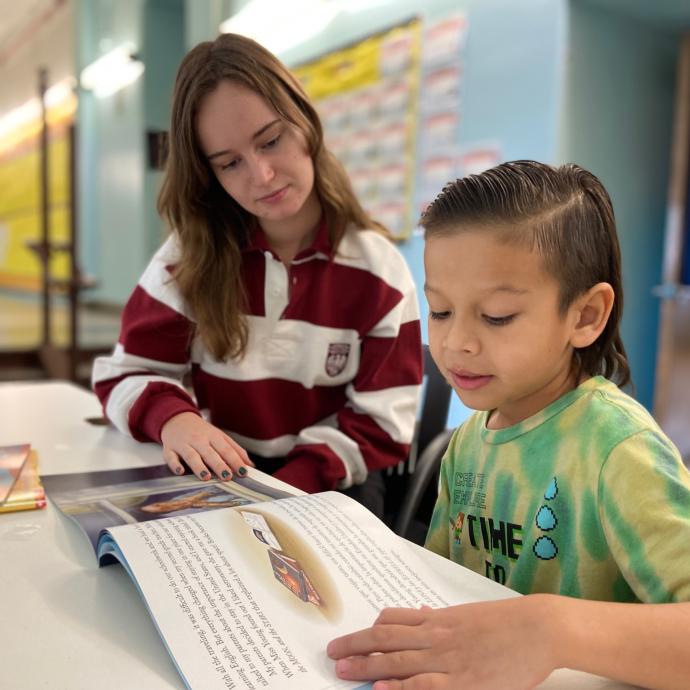

The Library donated intellectual labor, training graduate students on how to process the massive collection for the archive project Goldsby directs, “Mapping the Stacks,” which organizes archival information on Black Chicago from the 1930s to 1970s. The Library also made a path-breaking commitment of technological resources.

The University will create and maintain a permanent digital archive that will house a large selection of the more than 4,000 photographs in the Abbott-Sengstacke Family Papers. The University Library will ensure the accessibility of the visual archive. “If the standards and formats for preserving digital master files change,” says Schreyer, “we will move with the standard. That’s part of our commitment to this collection.”

What’s extraordinary about this commitment, Goldsby adds, is that it is in perpetuity. “That’s forever. Last I heard that was a mighty long time.”

It is not a small investment. Storing the digitized version of images, which are saved at high resolution, will require significant server space. In addition to the photo archive, the Library has created a website for Mapping the Stacks and will create and maintain a database to house the finding aids that Mapping the Stacks is producing, together with finding aids produced by the University Library as part of the Uncovering New Chicago Archives Project.

The University’s role in providing these technological commitments was an important factor in Sengstacke’s decision, Goldsby says.

Of the Library’s role in securing an acquisition for the Chicago Public library, Schreyer says, “Keeping it in Chicago was very, very important to us. As archivists, we believe very strongly that one of the most important aspects of a collection is context. These are not random pieces of paper. It is a collection that has provenance. Where it came from, and how it was created, links it to its future as well as its past.”

Because of its role in preserving the digital archive, the Chicago Public Library has given the University permission to use selections from the Collection’s digital images for coursework and scholarship without having to visit the Harsh Collection. Low-resolution copies of images from the archive will be made accessible online to University faculty and staff.

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He