Nearly every stone and seed in the new garden outside the Office of Multicultural Student Affairs reflects a part of the South Side of Chicago's history. The stone planters are remnants of pavement from Maxwell Street, the once thriving street market on the near South Side. A decorative chair occupied a spot in DuSable High School's auditorium in 1935. Even the stone where the dedication plaque is mounted is a nod to Washington Park's Roundhouse Building from 1890, where police once housed horses.

When the idea of converting the parcel from a patch of grass into a garden was first introduced, the student advisory committee for the proposed project had only one requisite - the dedication plaque must bear the name of a local hero who can recount just as much of the community's past, Timuel D. Black. This fall, University students, staff and community residents unveiled the 5710 S. Woodlawn Edible Arts Garden dedicated to Timuel D. Black.

Neither the garden nor 90-year-old Black display their full brilliance at first glance, but after a few moments of indulging Black's eloquent narratives or exploring the garden's diverse contents, the untrained eye can clearly see how much both have to say about the South Side.

Black's family moved from Alabama when he was an infant and raised him in the neighborhoods of Bronzeville and Hyde Park, where he still lives today. "I can walk to every site I've lived in from where I am right now," he said proudly. Today, he is affectionately recognized as the social justice griot of these communities, regularly conducting historical tours of Bronzeville for the Hyde Park Historical Society and the University's Graham School of General Studies.

His initiation into the life of a political organizer came while he was a student at DuSable High School. In the '30s and '40s, whites owned most of the small businesses and were reluctant to hire blacks. "We organized and had a slogan: 'Don't spend your money where you can't work'," Black said. When he did land a job at a local retailer, he noticed that white workers were offered more pay, better hours and more vacation time. Because black workers were not allowed to join white unions, he and his older brother formed a local chapter of the Retail Clerks Union and successfully challenged the inequities.

His penchant for challenging discriminatory policies and organizing others who supported his causes intensified during his service in World War II, when he trained in the South and fought in Europe. "I saw how terribly blacks were treated [in the army]. I would be shopping, and someone white could come and get in front of me. I saw the divided washrooms," he recalled. "I saw how a person like me in uniform could go and protect this country, fight for democracy, but not be able to enjoy that democracy myself."

An experience at a German camp "where people were scientifically exterminated," completely reverted his life's direction. "I realized that what I saw could happen to anyone. I decided that if I was going to risk my life to make this a better world I had to start where I am."

This led him back to the South Side where he continued to challenge racial discrimination at various Chicago schools through the Teachers Committee for Quality Education and through his work as local president of the Negro American Labor Council. In the position, he organized a faction of 3,000 Chicago passengers to participate in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He even organized a chapter of Congress of Racial Equality while earning his graduate degree in the University's Social Sciences Division. After years of requests, Black recently wrote two books: Bridges of Memory: Chicago's First Wave of Black Migration and Bridges of Memory Volume 2: Chicago's Second Generation of Black Migration.

"He understands the power of direct action and nonviolence, but brought a different perspective that people could collaborate without always agreeing," said Bart Schultz, Director of the Civic Knowledge Project, an initiative housed in the Division of the Humanities that brings a collaborative, social justice perspective to community engagement efforts within the University. Schultz originated the idea of plotting the garden with a social justice theme to prompt more conversations about the South Side's history and future. "I think Tim Black is really brilliant at keeping these conversations going and helping young people build those bridges of memory, so they understand that the struggle continues."

At the ceremony, Black said he was "quite surprised" to see that so many young people, a group he has worked with his whole life, were honoring him. The garden is a powerful metaphor for the motivation behind his work and its potential for the future. "It represents, in my opinion, the accomplishments that can be had if we persistently water the human garden and give it a chance to grow," Black said at the ceremony. "It's important for you young people to know that before you, people were working to make the garden grow and grow so that those who preceded you could feed another generation."

The hope is that the garden will serve both practical and philosophical purposes. Students are exploring ways to distribute the garden's assortment of fruits, herbs and vegetables through local food pantries while its historical elements will function as a backdrop to continue conversations about social justice.

"I wanted to make it a very collaborative work and use it for a larger purpose - to help people think of new forms of the fight for social justice, addressing problems of environmental injustice, which on the South Side disproportionately affect African Americans," Schultz said. "And I wanted it to be a tribute to Tim Black that helps people think the way he does about these issues."

For more information on Timuel Black and the Civic Knowledge Project, please visit: http://civicknowledge.uchicago.edu/

By Kadesha Thomas

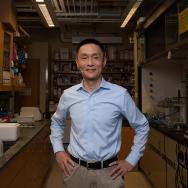

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He